Making a film is hard. Even to make an average, low-budget one, you need actors, a competent crew, locations (and permission to film on them), loads of technical equipment, and at least a five figure budget. British film is booming, but it’s only a certain type of film that seems to get made. If you want to do a period drama with Eddie Redmayne and Benedict Cumberbatch, it’s no probs. But if you’re a working class kid, not in the industry, if your dad doesn’t have connections, if you can’t afford to intern for a year with no pay, good luck getting very far in the film world.

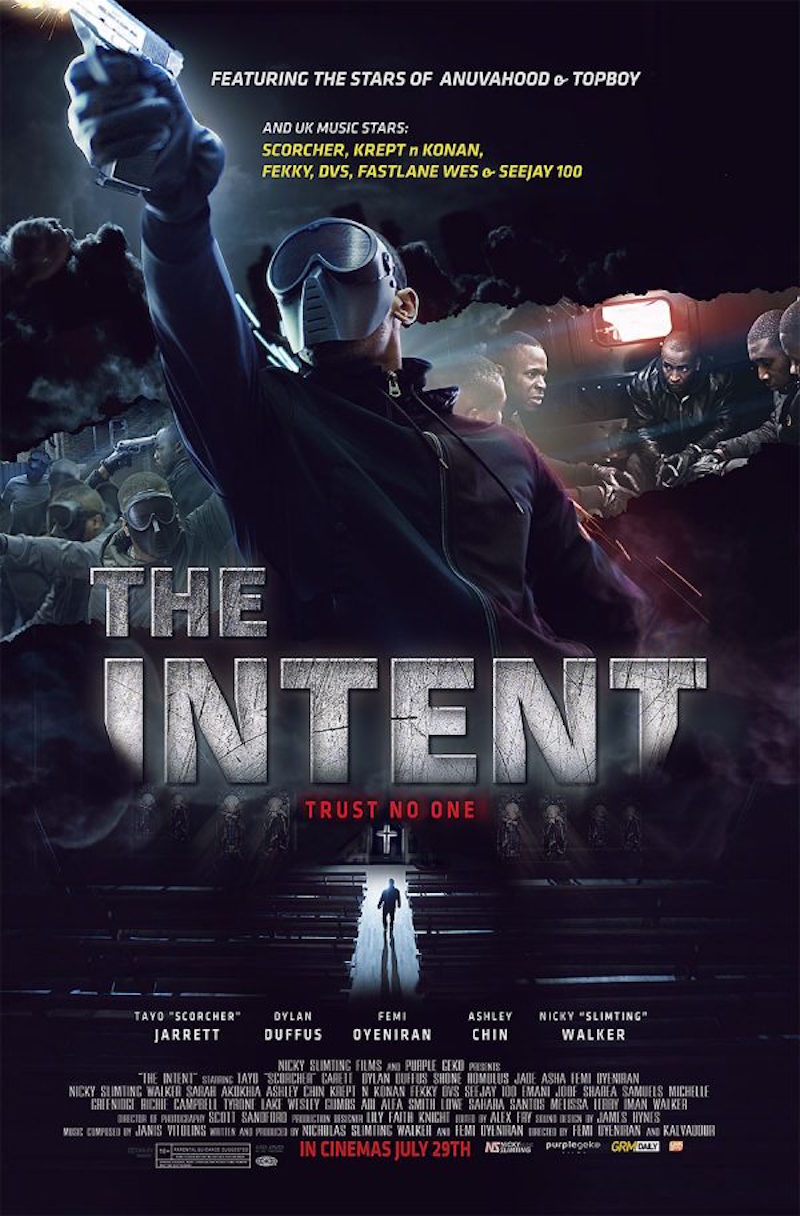

You’ll probably recognise Femi Oyeniran best as Mooney in Kidulthood and Adulthood. The Nigerian born, London raised actor got his break aged 17 when he when attended open auditions for the first movie. In the ten years since he’s managed to get two films written and directed by him made, completely independently — the 2013 comedy It’s A Lot, and the upcoming crime thriller The Intent. Just getting these films made is a real achievement — here is an immigrant fighting and hustling to get things done himself, and portraying a black London life that’s rarely seen on-screen. With The Intent set to drop at the end of this month, we caught up with Femi and his co-producer Nicky ‘Slimting' Walker (who made his name as a DJ in the early days of grime), and asked them how what advice they’d give to aspiring filmmakers, and how hard it is to get their films made, and just as importantly, actually in front of audiences.

rappers have more cache with the audience than with new up-and-coming actors

One of the first thing that comes up is knowing the market — and most importantly knowing your audience. It’s A Lot was a teen comedy in the Ferris Bueller / American Pie mould, a genre that tends not to do well in British cinema (unless it’s The Inbetweeners). “It’s A Lot struggled to find a position. It did alright, and it still continues to on Netflix, but it struggled to find a position.” Oyenrian admits, “So for us it was important that we work backwards, with the audience first.” That meant tapping into the grime scene that they grew up in. “We the examined the landscape, and the people that had the biggest following were the rappers. And then we thought about the films we liked when we were younger - Juice, Belly, In Too Deep, hip-hop classics. So we decided we wanted to do something with rappers, because they’ve got more cache with the audience than new up-and-coming actors, and create something that paid homage to the hip-hop movies we grew up watching.” Thus, the lead role was taken by Scorcher (who’d previously acted in Top Boy), with former DJ Walker using his links to the music world to have the likes of Krept & Konan and Fekky take other parts in the film (since making the film, Krept & Konan went on to top 10 success with "Freak of the Week", so it’s worked out very well in the long run).

So once you’ve got the idea, where do you actually get the money to make an independent film? “There are three models. There’s government funding. Then there’s funding schemes like Film London, Microwave, Creative England, iFeatures.” Then finally, there’s what funded The Intent: the private equity model. “We found investors that we knew would back this kind of project. We basically begged them for money, and made a business case for the film. But at the same time, they believed in us, and what we’re trying to create, so it was all mutual.”

We’re selling direct to the audience ourselves, there’s no middleman. We are the distributors, we are the marketers.

This source of financing is important, as the people with the money were on the same page and that meant he didn’t have to compromise the film to make it more commercial. “Our investors are mostly black, let me be straight.” Oyeniran continues. “I think every one of our investors so far has been black actually. They are mostly black guys who grew up watching the films we were speaking about, and they’ve just got their own businesses or whatever. So I supposed that helped, because they get it.You don’t have to water it down, to make it more commercial, to get more artists or more actors that would resonate with a mainstream audience. We didn’t have to make it mainstream, we just wanted to make it a street film. And do it in a way that if all goes wrong, we can sell it ourselves directly to the audience. And that’s what we’re doing. We’re selling direct to the audience ourselves, there’s no middleman. We are the distributors, we are the marketers.”

I wanted to go back and ask why they never went down the arts funding route (It’s A Lot had a small amount of non-financial script editing assistance from the BFI, but that’s it). “I have applied for a few things, but I’ve just not got them. And sometimes you’d rather just make the film, I’d rather make The Intent than sitting around. I rather make it for six figures than wait for seven figures to land. And I feel like a lot of government and arts funding is being cut, and a lot of the stuff that gets commissioned does not have a diverse outlook….The people who are making the decisions are middle class and white. I’ve had two meetings recently for funding; one of them had five people, and one of them was a black woman. And the other meeting was all middle class white people. And it’s hard for people to make decisions against themselves, or do things that do not fit into their worldview. And the decision makers are of a certain creed, so the films that get made are of a certain creed.”

You just need to hustle. Network. Go to events. You never know who you’re going to meet in the audience.

Oyeniran says that if you’re not from a privilege background, and if you weren’t born into it, it’s all about just getting out there. “I started acting when I was about 17, so I met a lot of people in the industry. I only got into Kidulthood because I went to an open audition. But for someone else, I think you just need to start making films. Make short films, enter them into festivals, apply to all the funding schemes. Film London have about three or four that you can apply too. They’ve got Microwave, they’ve got London Calling, and London Calling Plus specifically for people from BAME backgrounds. Creative England, which is for outside London, have development funding. They have iShorts funding (for shorts), and they also have an iFeatures funding (for features). That’s available to anyone with a certain level of experience, so you have to have made stuff — if you’ve made three or four short films independently of a good quality, then I think you should be applying for these things. The BFI have funding you can apply to. So go on their websites.”

“But at the same time, you just need to hustle. Network. Go to events. You never know who you’re going to meet in the audience. We’re having a meet and greet screening at Hackney Picturehouse, on July 29, try to get down so you can meet us. We’re having a preview screening in Birmingham, get down there, meet us. Be around, make sure you’re around it. Get a job in the industry. Work at a cinema, or a theatre. The difference between you and the other person who’s dad’s a producers is that they grew up around it, and they know the industry. So do it your own sort of working class way.”

working class and black kidS know how to film, edit, do everything, but they don’t know how to apply that in a professional setting

One place Oyeniran feels there’s the biggest lack of diversity is behind the camera. The Intent has a mostly black cast, yet he says it was a predominantly white crew. And that’s pretty common problem across the industry. “It’s actually embarrassing. I think it’s mainly because people from working class and BAME backgrounds — and I say working class because it’s not just a white / black thing, this includes white kids as well — do not know what job opportunities are available in the industry. They don’t know what they can do. They don’t know they can be DoP, they can be this, they can be that. There’s no outreach from the industry to try and get them in. You’ll meet a young working class or black kid, and they’ll know how to film, edit, do everything, but they don’t know how to apply that in a professional setting.”

I had a distributor saying to me “What are the big urban platforms nowadays? You’re going to have to help us get in touch with them.” Why would I give you such a percentage of my film, if you don’t know what you’re doing?

Oyeniran and Walker are releasing The Intent completely by themselves. This means they are they have a bespoke release strategy which fits the film and its audience. Cinema-wise, they’ve teamed with OurScreen which allows people to book the film in advance, and if enough people do that, the screening goes ahead. “That’s a cheaper model, and it puts control into the hands of the consumer.” They’ve also ‘four-walled’ a few screens - an industry term for buying out the screen in advance, and then taking the box office themselves. On the physical side of things, there’s a limited edition DVD with custom art, and 50 random pre-orders winning merch, props and signed scripts. It’s all grassroots things to engage with the core audience. Then there’s also the soundtrack album, featuring the likes of Ghetts, Jme and Frisco.

It’s A Lot was released by a small UK distributor, who bought the film off them. Why did they do go it alone this time? “We don’t believe in the distribution landscape. There’s no one like you or me in distribution. It’s all middle class people who don’t really know the scene. I had a distributor who wanted to do a deal saying to me “What are the big urban platforms nowadays? You’re going to have to help us get in touch with them.” Why would I give you such a percentage of my film, if you don’t know what you’re doing? I’m only giving it to you for the access to iTunes etc. So why don’t I find someone who can give me access for less of a percentage, and I’m in more control. We had offers from distributors, but we just didn’t take them, because we thought they couldn’t do it justice like we could.”

That Video On Demand access is vital. The cinema release, DVD and Blu-ray, and VOD release all drop on the same day — it’s about making it as easy as possible for people to see the film, so they don’t turn to piracy. But the access to streaming service like iTunes, Amazon, Sky, Playstation and Xbox has it’s own barriers — they’ve teamed with a company called The Movie Partnership, who act as a online distributor. “There’s a few companies who do that with independent filmmakers. If they like your film, they do a deal with you and take a cut, and help you approach all these platforms. They have access. All these platforms have preferred vendors, so they wouldn’t take a film from you or me direct, only from someone like The Movie Partnership. iTunes say, probably have about 40 companies that supply them with films in the UK. And if you’re not on that list, you can’t go to them direct. All these platforms have barriers to entry. I had a distributor say “You have to do a deal with us to get your film on iTunes”, but I knew I didn’t because I knew about these people."