Within the first minute of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt’s second season, Kimmy lets out a deep, uncomfortable belch. She’s in the middle of giving a characteristically cheery monologue about the holidays, about the people in her life, when the foul burp makes its way to the surface. Lillian, Kimmy’s kooky, gentrification-hating landlady, is taken aback at how something so vile can come from someone so sweet. She suggests, lightheartedly, that Kimmy should go see a doctor: “It’s like a mouse died in the walls of your body.” Kimmy’s trauma burps, as we soon understand them to be, become an ominous symbol throughout the first half of the new season, a constant reminder that underneath her delightfully cartoon-y sensibility is a person who is severely damaged after spending a bulk of her life imprisoned in an underground bunker. She has a lot to sort out, and really only starts to face her issues after accidentally becoming the Uber driver to Dr. Andrea Bayden, an alcoholic psychiatrist played by Tina Fey.

The relationship between television and therapy isn’t new, and has, for so many years, been a handy device used by writers to develop characters, plots, and themes both superficial and subtextual. Therapy’s pervasive presence makes all the more sense on TV considering that the medium, particularly in the era preceding binging and streaming, evokes a 30-minute to hour-long weekly therapy session. You lay on a sofa, engage and somewhat interact with the elusive presence in front of you, and after you’re finished, you spend the remainder of your week in a mixed state of anticipation (and maybe even dread). It’s really no surprise then that TV has made use of therapy on Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, but also on M*A*S*H, Frasier, The Sopranos, Arrested Development, Mad Men, and in one of the biggest TV moments ever, on Ellen, when Ellen DeGeneres’s Ellen Morgan realizes she is gay and is encouraged by her therapist to come out to her friends.

As someone who has seen his fair share of therapists over the years, I have always been fascinated by the way television interacts with therapeutic institutions and discourse. There’s the more blatant example of The Sopranos, which preoccupied itself with Dr. Melfi and Tony Soprano’s conversations, but even in more recent shows like Broad City, Empire, The Leftovers, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, and The Americans, where therapists aren’t necessarily the focus, we still get a sense that the creators and writers are concerned with parsing out the psychology of their characters. This may have always been true about TV, but until recently I never considered how the confluence of therapy and TV has led TV to function as its own sort of therapy for the viewer, one that begins to exist outside the console.

Two weeks ago, Netflix released a new original series, Lady Dynamite, a comedy that delves into the psyche of a fictionalized but still very real version of the comedian Maria Bamford. We are immediately privy to Maria’s breakdowns and breakthroughs, and there’s a scene that occurs midway through the season where Judd Apatow appears to offer Maria a role in his upcoming Bridesmaids and Ghostbusters mashup. He tells a surprised Maria, “Maria, you’re doing that thing again. That thing where you diminish yourself as a person and an artist ‘cause you’re afraid to accept that you have a unique and singular voice.” You feel a pang in your chest. Perhaps you bury your head into the body pillow you hadn’t realized you’ve been grasping onto the entire episode. You may even take screenshots of the scene, captions on, and send them out to Twitter, to a network of friends, family, and strangers who need to see this truth you’ve stumbled upon. And it’s this mixture of pain, pleasure, but more than anything, a feeling of understanding and relatability, that has made TV such a crucial component of my existence.

When it comes to TV, I have always been a feeler first and a critic second. A few years ago I started watching Enlightened, the brilliant and short-lived HBO comedy about Amy Jellicoe, an erratic, earnest, ambitious, but emotionally volatile woman with a very black and white sense of justice. In the pilot we see Amy, an executive at a huge company, have a nervous breakdown in a bathroom stall at her workplace. Following her fall from grace, she seeks rehabilitation in a New Age-y facility in Hawaii and returns all zen, frizzy-haired, clear-headed (somewhat), and determined to not only get her job back but affect change in the world. As a result of her transformation, each episode culminates in a thoughtful and soothing Jellicoean voiceover:

None

I ate that up, and continue to have similar revelations in several of TV’s current offerings, including the latest season of Showtime’s gothic horror series Penny Dreadful, Sundance's Southern drama Rectify, Netflix's BoJack Horseman, and Australian comedy Please Like Me. The little-seen but much beloved show follows a young man in his 20s who comes out as gay in the pilot episode and must not only learn how to embrace his identity, but must also do so with a manic depressive mother and a boyfriend with the most debilitating anxiety. Besides their one-liners and scenes so rich in pathos, these series are all about self-betterment, and at some point in developing an attachment to their characters’ happiness—supported by the fact that we are getting to know them better week to week (hour to hour if you’re binging)—I find that I am also wanting happiness for myself.

In season three of the delightful Please Like Me, Josh, the show’s lovably aggravating main character, is lying in bed with Arnold, his boyfriend who suffers from a pretty severe anxiety disorder. Josh asks Arnold, “What can I do to make today less shit for you?” Arnold says, “Love me.” Josh replies, “Okay, done. Nailed it.” And I’m gone. I feel a warmth wash over me and at some point in my day I’ll remind myself how important it can be to ask someone you love, someone you love who suffers, what you can do to make things easier. It’s a simple, not pushy wisdom that feels right to give and to receive from the world.

But why and how do I get to a point where I feel like what is being said on TV is wise, and a form of therapy? In Emily Nussbaum’s recent essay on Lady Dynamite she writes, “As with HBO’s Enlightened, Lady Dynamite is a show that frequently satirizes New Age and therapy speak but that nonetheless has faith in their bedrock ideals.” Both series begin with a mental collapse, one grand episode of lack of control that the characters spend an entire season and, in the case of Enlightened, series, trying—with varied levels of success—to move past. Both Amy Jellicoe and Maria Bamford are entirely earnest, fundamentally absorbed by hopes for a happy and stable future, and spend their time espousing the kind of rhetoric that’s continuously becoming less and less stigmatized in our day to day. Essentially, the therapy-speak Nussbaum alludes to in Lady Dynamite is really just the way we’ve come to talk and think and relate. Maybe we all have faith in it.

There’s a brutal but hilarious scene in “Bisexual Because of Meth,” Lady Dynamite’s second episode, where Maria goes on a date with a man who overshares as much as she does. She has bipolar II, is consistently anxious and uncomfortable, and is just all around pretty wacky. But she’s unapologetic and has no shame in revealing this info to her hot date. After the man guiltily confesses that he sometimes misses self-medicating with meth, Maria shares that she misses the exact opposite. “That’s not weird at all,” she reassures him after his confession, and goes into her own desire to be off her meds. “I miss the energy of mania. I may have been contemplating suicide 18 hours a day, but my baseboards were spotless.” They talk freely about the worst parts of themselves, and in this exchange they offer their own sort of reassurance for the viewer. In part, Lady Dynamite is about being kind to yourself, whether it’s by strapping a paper tray of Fritos to your adorable pug so you don’t have to move much to snack or refusing to date people who put demands on you and shame you for your quirks.

The New York Times recently published an essay called “Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person.” A line in the second paragraph stands out: “In a wiser, more self-aware society than our own, a standard question on any early dinner date would be: ‘And how are you crazy?’” Although we’re talking about different institutions, today's TV is doing such a good job of relating through insanity and suffering—and through the hope that it'll get better—that I feel as moved and disturbed by it as I do when I walk out of my shrink’s office.

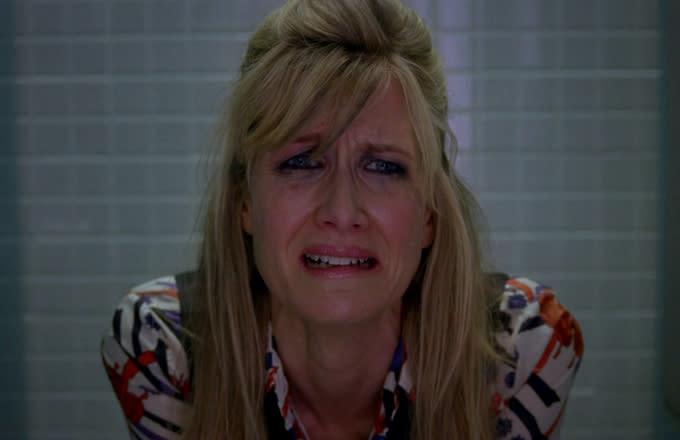

It’s not only Lady Dynamite that celebrates embracing one’s demons and trying to push past them—Kimmy Schmidt does it too. It’s how the comedy series earned that "unbreakable” adjective. “Kimmy Meets a Drunk Lady,” the ninth episode of the second season, exemplifies this best. Kimmy first meets Dr. Bayden after she has spent a late night out. Dr. Bayden is blackout drunk and gives some severe, but significant life advice to Kimmy and, while drunk, pressures Kimmy into becoming her patient. By day she is more composed and reluctant to take Kimmy on as a client considering how unprofessional and unethical their early encounters are. Still, despite going in circles with drunk Dr. Bayden and stable Dr. Bayden, Kimmy is steadfast and determined to finally seek out the help she needs.

And as absurd as the whole scenario is (playing Uber driver to your alcoholic therapist by night and patient by day), it’s Kimmy’s efforts that rub off. As she walks into Dr. Bayden’s office one morning to make a final plea that she be taken on as a client, Kimmy pulls out a video drunk Dr. Bayden recorded for her sober self. “You know you want to shrink the eff out of that busted little walnut brain in a clown wig,” drunk Bayden states. And in agreeing with her, with wanting Kimmy to get help, I want to be better for myself too.