Radiohead’s eerily prescient music—and the band’s enigmatic presence in an ever-transparent world—has always been ripe for conspiracy. There’s the theory that the “A” in their 2000 album Kid A isn’t a moniker for the first cloned human after all (contrary to another popular belief) and that it instead stands for their follow-up, 2001’s Amnesiac, because, as the fan theory reads, “Amnesiac is about a personal struggle, and Kid A is a description/account of that struggle.” Another infamous one, from writer Chuck Klosterman, argues that Kid A unwittingly predicted 9/11. And then there’s the “Binary Theory” (or “TENspiracy”), which holds that both OK Computer (1997) and In Rainbows (2007)—the latter of which is said to have held the working title Zeroes and Ones—were consciously conceived as one superwork and that their songs fold seamlessly into one another when placed side-by-side with a 10-second crossfade in between.

Whether these conspiracies are true is anyone’s guess; the band is either maddeningly reticent or cryptic in interviews, neither confirming nor denying anything. “We’re dead set on the music,” the group’s Phil Selway said of people’s attempts to read into the puzzles. “That’s the thread running through this whole thing. We met at school playing music together, and we still get together over music now. We like solving musical puzzles.” Yet practically everything Radiohead does (or doesn’t) is subject to scrutiny, and serves as fodder for further conspiracies to develop. And while this sort of fan-driven speculation isn’t unique to Radiohead, the theories surrounding them concern their music instead of their personal lives. That's more than can be said for the theories surrounding the likes of massive pop acts, like Katy Perry (JonBenet Ramsey actually?) or One Direction’s Louis Tomlinson (fake baby?).

Radiohead conspiracies are ramping up again, though, given that they teased their ninth album, the plucky, dread-laced A Moon Shaped Pool, with a series of characteristically ambiguous clues. First, in late April, they sent out leaflets in the post to some fans with the words “Burn the Witch” emblazoned on them (words that, fans noticed, appear on the album art of 2003’s Hail to the Thief). On May 1, they wiped their entire social media slate clean, from their Twitter account to their website. The next day a teaser video followed, featuring a claymation bird chirping in an endless loop (colored blue, like the Twitter bird!). That led to the peculiar video for the album’s first single, “Burn the Witch,” a stop-motion claymation venture released last Wednesday that nodded to the 1973 cult film The Wicker Man and 1960s-era British children’s television shows like Trumpton.

New theories developed milliseconds after the video’s credits rolled. One Reddit theory read the band’s social media disappearance through the lens of their unreleased song “Silent Spring,” and paralleled it to International Dawn Chorus Day, held on the first Sunday in May, where people are encouraged to get up early and listen to bird songs together. Citing the “withdrawal of information,” user bornjoke writes: “Imagine waking up one day and the songs of the birds are no longer there because how humans treated the planet [and] killed them all off.”

The question of environmental catastrophes aside, there’s also the question of surveillance in the world. To wit: the “Burn the Witch” leaflets sent to fans featured the words “we know where you live” on the bottom. Could it be that Radiohead was making the concept album about whistleblowers uncapping the NSA’s all-encompassing surveillance? Did one of the overlords of millennial despair, Edward Snowden, provide guest backing vocals all the way from Russia? Would the new album be released via carrier pigeon, given the band’s disappearance from social media and Thom Yorke’s vocal disavowal of Spotify? (A Moon Shaped Pool was released via Apple Music).

100% chance that the new radiohead features multiple snowden references

The premature conclusion that A Moon Shaped Pool could be the opus of the Brave New Digital World variety isn’t unfounded. Back in ’97, the critically lauded OK Computer anticipated the rise of sentient technology, and how it’s caused us to splinter from each other in real time, through imagined tales of paranoid androids, tired aliens pining for their home planet, and robot-spouted interludes calling out the cult of self-improvement. And then there’s the album’s big single, “Karma Police,” and how it’s been put to more sinister use as of late. The Intercept reported earlier in 2015 that the song doubled as the title for a cover surveillance operation by a British mass surveillance operation from the Government Communications Headquarters that kept “billions of digital records about ordinary people’s online activities” from “visits to porn, social media, and news websites, search engines, chat forums, and blogs.”

But as far as Radiohead’s music goes, perhaps we’re going too far in suggesting it has a hand in disarming a global conspiracy. The new Paul Thomas Anderson-directed video for A Moon Shaped Pool’s second single, “Daydreaming,” released last Friday, seems to want to be taken at face value. In it, Thom Yorke traipses through beaches and residential homes, opening door after door while crooning about dreamers. It’s not so much deceptive as it is utterly mundane, displaying how exhausting just living can be before eventually laying down in a cave and sleeping forever, as Yorke does in the end of the video. Sure, the band’s preoccupation with paranoia is still there (in the opening shot, several dark-cloaked, sinister figures in the distance appear to be following Thom Yorke into a parking garage). But at the core, “Daydreaming” may just be that the band is dreaming about where those other doors, long since closed, might have led instead.

One of those daydreams may very well be a parallel universe where Radiohead doesn’t harbor fears of being bombarded with camera phones when just trying to walk to, say, a laundromat. There’s traces of that sentiment on Moon’s lovely piano dirge “Desert Island Disk,” on which Yorke warbles, “Through the doorway/I cross the street/Into another life.”

The way we’ve deified Radiohead, and our desire to see how their music causes everything to fit in its right place, is precisely why they’re so taciturn (and, for some of its members, explains the near-hermetic periods in between touring for albums). It’s also why they disappeared, almost completely, during the late-’90s. “Everyone comes to us with their heads bowed, expecting to be inducted into the mystery of Radiohead,” Phil Selway told The New Yorker’s Alex Ross in 2001. “At a certain point, around 1997, we were simply overwhelmed and had to vanish for a bit. This was our honest reaction to the situation we were in. But some people thought we were playing a game, or had started taking ourselves too seriously. Really, we don’t want people twiddling their goatees over our stuff. What we do is pure escapism.”

The thing is, what keeps fueling these conspiracies is the fact that the kind of escapism Radiohead probes in their dense music always feels supernaturally well-timed. They release music in a painstakingly deliberate, measured way, and somehow always at a time when generational dread is cresting a new and terrifying peak. In the past, they’ve anticipated a near-future dystopia (OK Computer) and lashed out following George W. Bush’s contentious presidential win with Hail to the Thief, an album that also featured a direct nod to George Orwell’s 1984 (“2+2=5”). A Moon Shaped Pool is just as immediate, from its opener “Burn the Witch” and its reference to “a low-flying panic attack” to the image of a “spacecraft blocking out the sky” leaving us “nowhere to hide” on “Decks Dark.” As Pitchfork’s Marc Hogan writes: “The ‘Burn the Witch’ video plays as a pointed critique of nativism-embracing leaders across the UK and Europe, perhaps even the show's near-namesake stateside (Donald Trump, anyone?).” And who can blame them for tackling uncertain topics in uncertain times? Somebody’s got to. In fact, this is what good art should do.

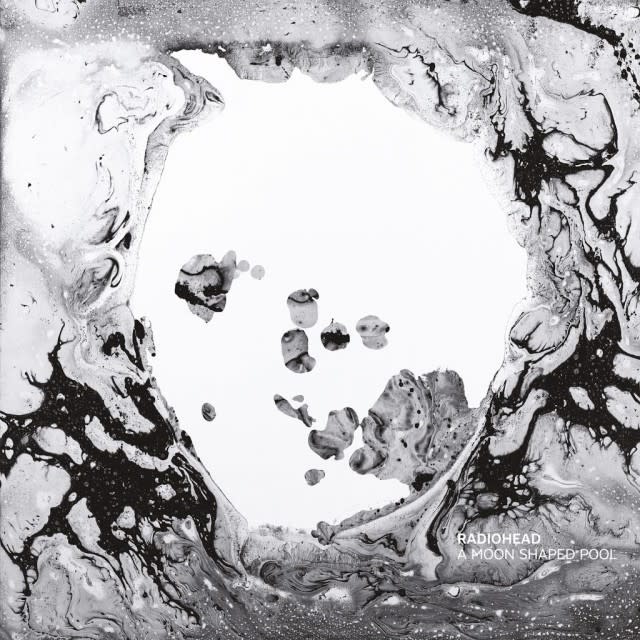

The conspiracies surrounding Radiohead’s music are bemusing, and can certainly be fun to contribute to and connect with. But our culture’s nascent impulse to interpret every move they make and create, from Slenderman-esque album artwork to visual diagrams is, as the group’s Phil Selway once put it, “a bit incidental.” The impulse to dissect everything is at once a tenant of diehard Radiohead-head fandom and enabled by the Internet’s all-encompassing way of leaving no stone unturned. It isn’t helped either by the fact that Radiohead releases music at a pace considered glacial in this instant gratification era, leaving much time to obsess over what these words might mean years later. While it won’t be long before fan threads attempt to decode what phases of the moon constitute this moon-shaped pool, and why the songs are alphabetically arranged, the secrets are already being whispered in your eardrums.

In the same way that all art is undeniably informed by the time when it’s created, A Moon Shaped Pool serves as a timestamp for where we stand now: adrift, in uncertain tides, feeling marooned by the very technology that’s supposed to bring us closer together. And while the album simmers with dark grooves and subjects undulating under a stunning surface, there’s something uncharacteristically hopeful about it: Even blistering, beautiful tunes like “The Numbers” suggest that we have more control than we realize in this uncertain time. Even Radiohead used to think there was “no future left at all,” as they proclaimed on Amnesiac’s “I Might Be Wrong” back in 2001. Now, the “future lives inside of us,” Yorke sings. “It’s nowhere else.”